- Home

- Julie Rieger

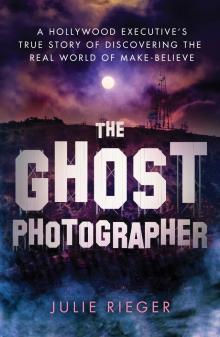

The Ghost Photographer

The Ghost Photographer Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

This book is dedicated to my mom, Margaret Hadley. Here’s the only way I know how to characterize this dedication: It’s a love letter from a daughter to a mother.

Mom, I will never forget the day you said to me, “I knew exactly who you were the minute you were born.” I’m pretty sure we have both always known that this wasn’t our first lifetime together. You showed me unconditional love, effortlessly. I miss you being here. I miss your wit, your intelligence, your compassion, your love of Consumer Reports and Cat Fancy, and your unwavering love of Neil Diamond. I miss sitting across the table from you in full view of your refrigerator magnet that read: “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.”

You taught me to be kind; even when the other person didn’t deserve it, you assured me that they needed it. The pain of losing you is so enormous that it can’t possibly disappear entirely. The pain is just a part of me now, like an appendage.

What made you such an extraordinary mom is that you loved me for exactly who I am, for just existing on this planet. I can only hope we get to do this again. I would be your kid all over again, and again—for infinity.

INTRODUCTION

Stumbling into the Cosmic Wilderness

But once you have a belief system, everything that comes in either gets ignored if it doesn’t fit the belief system or gets distorted enough so that it can fit into the belief system. You gotta be continually revising your map of the world.

—ROBERT ANTON WILSON

Freedom is what’s left when the belief systems deconstruct.

—DANA GORE

Shit happens. We all have stories about events that changed our lives, but it’s the big ones—the life crises, the serious wake-up calls—that fundamentally reconstruct who we are. Grief was the dark alchemy that shook up my world. It blew open a door to the Other Side—and yes, I am talking about ghosts, spirits, and etheric creatures that looked like they’d pranced right out of a movie.

People come into their psychic powers in different ways. Some people are born with them. Others have to die first and actually come back to life. And some folks develop psychic powers after they’re literally struck by lightning. Well, ghost photography was the lightning rod that set my previous life ablaze, but thankfully I didn’t get electrocuted in the process.

My transformation was not as dramatic as that, but it certainly was strange—and scary. I sometimes felt like I was at the summit of a giant roller coaster, looking down at the puny diorama of life on earth below and thinking: Uh, excuse me? Can you get me the hell off this thing?

Of course, there’s no turning back.

If grief was the catalyst that kick-started my journey, ghost photography was the path that led me into the cosmic wilderness. I had the good fortune of finding an exquisite psychic Sherpa who guided me through this strange wonderland, though I didn’t knowingly seek her out. And while there’s no argument now that could ever convince me that the physical world is all there is, I’m still the least likely person to be into anything “alternative” or spiritually woo-woo. I may live in La-La Land, but I grew up in rural Oklahoma—and those roots go deep, my friends.

In fact, for most of my life I didn’t even believe in ghosts. My family was not particularly religious or godly, either, though I was raised Episcopalian. (Episcopalians are the stepchildren of the Catholic Church.) I was also an acolyte, which meant that I walked down our church aisle wearing a white robe and carrying a cross. I had no idea why; my mom me told me to and I was an obedient kid. I think only boys were supposed to be acolytes back then; I had shaggy hair, and a few of the old churchgoing geezers actually thought that I was a boy. Talk about a real cross to bear.

I officially gave up on organized religion when I came out of the closet at age twenty-three. Christians didn’t seem to be big fans of the gays, so I decided not to be a big fan of Christians. We didn’t miss one another.

More important, my entire professional life is deeply rooted in the empirical world of hard numbers. I oversee the data strategy for a major motion picture studio and build data management programs that deliver insights into consumer behavior through data science, natural language processing, and analytics. I also manage complex media budgets with multiple zeros at the end of them. My official title is long and fancy: President, Chief Data Strategist, and Head of Media. (Essentially, I’m a nerd in the midst of some of the most creative people in the world.)

To say that my life didn’t exactly turn out the way I thought it would is an understatement. (I think that’s evident by the title of this book.) By all accounts I should be living in a big city in Oklahoma, married to my high school boyfriend with a few kids, and working somewhere cool like Krispy Kreme. (Okay, that’s just a sugary fantasy. How about the Tulsa World newspaper?) I thought that by overcoming stuttering and a few other childhood dramas, my battles were over. I thought that I could live a normal and peaceful life.

That’s not what happened.

I now lead a rather private—not to be confused with peaceful—life with Suzanne (my wife for more than twenty-five years) and our little furry children. My personality type doesn’t lend itself to peaceful. I am constantly doing something. In fact, I’ve gotten up at least ten times while writing this paragraph alone. I always have a project going on, whether it’s sculpting metal, rock polishing, throwing pottery, or doing something crafty. I once beaded a wooden tissue-box cover for a friend. It was absolutely hideous, but we all have to start somewhere.

Everything in my life collapsed the day my mother died. Grief, by the way, is like Baskin-Robbins: There are at least thirty-one flavors. There’s money grief, death grief, boyfriend grief, health grief, divorce grief, sex grief, fat grief, empty-nester grief, got-fired grief, presidential-election grief (I just added this one), and even something called Christmas grief (probably because you have to spend time with all the people who participated in this list). Sadly, grief is not a delicious concoction of milk and sugar churned together with a delicious bag of Oreos. Grief makes you question why you’re even alive. Nothing matters, not even ice cream. You lose connections to other people, then ultimately to yourself, which leads to isolation. And isolation is not just abuse to the body; it’s a jail sentence for the soul. Ever wonder why solitary confinement is the harshest punishment for our most hardened criminals?

But grief is also transformative, and it eventually catapulted me on a journey. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, mythologist Joseph Campbell wrote about the hero’s journey, a narrative that’s become a major trope for self-awareness: A hero has to lose himself before he “ventures forth from the world of common day into the region of supernatural wonder,” writes Campbell. “Fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

The concept of the hero’s journey has inspired millions of people and was partly the inspiration for George Lucas’s Star Wars, among other great tales.

My own journey was radical, transformative, and completely unexpected. That’s why I was drawn to Cheryl Strayed’s book Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail. Grieving the loss of her mother, Strayed hiked eleven hundred grueling miles solo across

the Pacific Crest Trail to find herself. She effectively had to survive her journey in order to thrive in her life. In so doing, she changed her personal story and the story that women are told about their limitations and place in society. She grappled with her fears until she embraced her own power. “I knew that if I allowed fear to overtake me, my journey was doomed,” she wrote. “Fear, to a great extent, is born of a story we tell ourselves, and so I chose to tell myself a different story from the one women are told. I decided I was safe. I was strong. I was brave. Nothing could vanquish me.” You go, girl!

I was lost and found in a different wilderness than Cheryl Strayed’s. Mine was a cosmic and spiritual wilderness that started with ghost photographs of disembodied spirits and fantastical creatures that sometimes looked like the very creatures in the movies I was marketing. In the course of finding myself, I found my sixth sense (and other senses that you’ll learn about later in these pages). I was able to communicate with spirit guides, spirit animals, and deceased loved ones. I started using magical tools like pendulums, prayers, crystals, and sage. I fought dark spirits and started to believe in God after a long breakup. I can’t turn metal into gold, but my journey through loss and grief was alchemical in its transformative power. In fact, virtually every aspect of my journey is alchemical in its transformative nature; some might even call it magical.

But like every roller coaster ride, the spirit world can be scary. I thought that I was a badass in real life, but I had to learn some hard lessons that even my spiritual tribe hadn’t prepared me for. I had to work my way through some serious dark stuff to become a real badass in the face of the unknown.

Every single fiber of my body now understands that we humans have spiritual power over disembodied spirits precisely because we inhabit bodies. This is our true, essential power, and it can protect us if we learn to harness it. You are in charge of yourself. You call the shots, not some incorporeal ghost or dark spirit. Use this knowledge from the Other Side for the good of yourself and others on this human side—in this world, on this earth—and you are protected. That is the heart of the journey I’ll share with you in these pages.

CHAPTER ONE

Sangria

Wild women are an unexplainable spark of life. They ooze freedom and seek awareness; they belong to nobody but themselves yet give a piece of who they are to everyone they meet. If you have met one, hold on to her; she’ll allow you into her chaos but she’ll also show you her magic.

—NIKKI ROWE

I come from a long line of badass women. My grandmother was the first woman to manage a men’s clothing store in Okmulgee, Oklahoma. Women didn’t do that back then. While determining a customer’s inseam, she’d shift their balls to the right or left without flinching. Odds are, hers were bigger than theirs. Ditto for my mom.

My mom, Margaret, was an accountant. She did bookkeeping for grocery stores, cattlemen, travel agencies, and oil guys in Oklahoma and Kansas. One cattleman never had cash to pay her, so he’d give her a side of beef or a whole pig. We had a Deepfreeze in the garage to house Mom’s paycheck. The good ole barter system was alive and kicking in rural Oklahoma.

Margaret was also a serious badass who intimidated most men. This was in the seventies, when feminism was in the national spotlight for this first time. But the seventies in, say, California or New York, was more like the fifties in Oklahoma: Women were supposed to be happy homemakers who tended to the needs of their men. Margaret was doing the work of a man at the time: She was an accountant who decided to computerize on her own with an IBM TRS-80 computer, which back then was a little like figuring out how to build a Mars rover with a can opener in your garage.

One of my favorite stories about my mom dates from the mid-1970s, when she was attending an all-male state tax commission meeting in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. After the meeting they had a fancy sit-down gala dinner featuring a “special drink”: sangria. (Anything other than beer and screw-top peach wine was “special” in Oklahoma back then.) All night long men would ask Margaret if she wanted a sangria, and all night she kept politely declining.

Finally, one guy asked her why she kept declining the drink. With a straight face she replied: “Because it makes my pussy twitch.”

Every year thereafter, my mom was greeted with: “Hi, Margaret. Would you like a sangria?”

Bottom line: My mom never adapted to being a real southern woman. In fact, she didn’t even try. She made the wrong food (no chicken-fried steak or Frito chili pie), wore the wrong clothes (no dresses, no frill, all-jeans-all-the-time), and had a foul mouth (the apple does not fall far).

To me, she was perfect. I was sixteen years old when she said, “I knew who you were the minute you were born.” Even though my mom was not particularly spiritual, I know that in that moment she’d tapped into her higher self; it was her way of saying that she could see into my soul. I’m not sure if it was also her way of suggesting that we’d come into this life together for a reason, or that we’d probably experienced who knows how many lifetimes together (and would no doubt experience many more). God knows why we all ended up in Oklahoma in this lifetime.

But we did end up in Oklahoma, and my formative years will forever be part of that ravaged state.

Oklahoma is, no surprise, a zillion cultural light-years from LA. For starters, I don’t blame the dust bowlers for coming here: Los Angeles on a shitty day is better than Tulsa on its greatest day. And it’s filled with beautiful people, literally, especially waiters and waitresses. They’re absolutely gorgeous, which makes me not want to go out to eat. That goes for people’s pets, too, by the way. In Oklahoma, dogs fetch. In LA, dogs are fetching.

The state is famous for its college sports and its oil. It’s not famous for diversity and tolerance. Its name comes from the Native American words “okla” and “humma,” which means “red people.” And that’s because the state originally belonged to Native Americans until the Indian Appropriations Act of 1889, when Congress forced them off their ancestral homeland via what was called the “Trail of Tears.” Years later those white folks deeded that same Indian land back to the Indians. Talk about a super shitty deal for the Indians.

Some pioneers (aka greedy-ass homesteaders) couldn’t seize the land fast enough and staked their claims on the nicest chunks of land before the official launch of the Indian Appropriations Act. Those folks were called “sooners,” which became synonymous not only with the state’s college football but also with anyone who snuck out in the middle of the night to claim their turf before the land rush.

I have no idea why the sooners were in such a hurry to get their land in Oklahoma; I couldn’t wait to get out of that state. Oklahoma was founded by some very bad dudes who were not only stealing other people’s land, they were stealing it before other potential thieves could get their hands on it. These real estate tycoons and developers raked in big bucks on the backs of the unsuspecting workers and laid the groundwork for today’s fat-cat developers who are doing the exact same thing. They are still ravaging the shit out of Oklahoma, never mind the rest of the world. They’re fracking for oil, robbing the school systems of financial support, inciting hatred through racism, and motivating people to turn to meth for money and escape. A tiny minority of morally depraved bullies is getting richer and richer doing all the wrong things, and they’re certainly not spreading the wealth around.

But okay, I digress. The thing is, I still have Oklahoma in my blood. It formed me. And though I see it now for what it truly is, it was my paradise growing up. I loved (and still love) many of the people I grew up with. I knew virtually everyone in town, from the gas station owner (where we got S&H Green Stamps and bought a set of encyclopedias) and the janitors at the local B. F. Goodrich tire plant, to fast-food owners, county clerks, and the local police.

The town I grew up in was a mix of Caucasians and Native Americans, and nearly every white person had Native American blood. (We were an anomaly because we’d originally hailed from the East.) I recall only one A

sian family who moved into town with two girls. Each one became a valedictorian and left the rest of us in the dust because we were a bunch of stupid white people who could not compete. (I say this with great respect to both Asians and stupid white people.) Some of my closest friends lived in a trailer park and we thought nothing of it. I wasn’t even familiar with the term “trailer trash” at the time.

I also didn’t understand the connection between experience and belief back then and I didn’t know Wiccan from wicker. When Sting was singing “We are spirits in the material world,” I had finally stopped bedwetting at the ripe old age of twelve. What the hell did I know about spirits in the material world? All I cared about was golf and riding my bike around undeveloped land in Oklahoma that’s now filled with Walmarts. The closest I got to the spirit realm was freaking out over the movie Carrie. Otherwise, I was all about the material world, and that material world was all about Oklahoma.

It was decidedly uncool to be gay everywhere in the world in the early 1990s, much less in Oklahoma. Telling anyone in my orbit back then scared the holy hell out of me; people were shunned, rejected, and physically or emotionally abused when they came out of the closet. Of all the people I didn’t want to risk losing by revealing my “secret” (all those who thought I was “awesome,” from my teachers to my relatives), my mom was on the top of the list.

I finally told her at the age of twenty-three in the lamest way possible: by phone. I was living in a dive in Dallas with my then-girlfriend, Suzanne (now my beloved wife), when I called my mom and just blurted out: “So, uh, Mom? I think I like women.”

Silence. Finally she asked: “You ‘think’?”

“Well, yeah,” I replied. “I think I know I do.”

The Ghost Photographer

The Ghost Photographer