- Home

- Julie Rieger

The Ghost Photographer Page 2

The Ghost Photographer Read online

Page 2

“Have you tried it?” she boldly asked.

“Of course.”

The line went silent. This was the moment, I figured, when I dashed all the dreams my mom ever had for me.

One week went by—not a word from her. Two weeks passed—nothing. Finally, the phone rang three weeks later.

“Hi, baby. I just got back from Judy Long’s house,” she said. “We had a long talk about you. I told her that you were a lesbian”—she pronounced it less-be-in—“and I admitted that I was having a hard time and that you weren’t who I thought you were. Judy cut me off right then and said, ‘Right, Margaret, she’s better; she can be happy now.’ And you know, honey? She was right. So, do you have a girlfriend?”

I just sighed and said, “Yes, I do, Mom, and you’ll love her. Her name is Suzanne.”

When Mom or I commit to something, we commit. In no time my mom had joined PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). She started hiring only gay-owned businesses to work on projects. She even hired my gay high school algebra teacher and her partner to paint her house during the summer.

Margaret loved me unconditionally. In fact, her three favorite words were “I love you.” It wasn’t until way later in my life that I realized not every mother is as awesome as mine. She was a natural-born feminist, too, and liberally doled out motherly advice that only a woman of her generation could. “You know, baby,” she’d say. “You don’t ever have to rely on anyone. You can do anything a man can do, if not better. Don’t feel like you ever have to get married. In fact, you don’t have to have kids, either. You can shack up and adopt if you want.”

How right she was. She was the light of my life, the hub of my wheel. She brought me into this world and then, unbelievably, she left it. And I do mean “unbelievably,” because I never believed that my mother would ever go away, nor could I have anticipated the depths of my grief when she did. My mom was like air or gravity, an incredible force of nature that I took for granted as a constant.

So much for the guy who said: “The only constant is change.”

CHAPTER TWO

Can’t Remember Shit

We are all the pieces of what we remember. We hold in ourselves the hopes and fears of those who love us. As long as there is love and memory, there is no true loss.

—CASSANDRA CLARE

I hate to break it to you, but here’s one thing that I can totally guarantee you: You’re gonna die one day. And that’s not all: You’re going to lose at least one person you love. We all come in one door and go out another, and we never know when our day will come. If you’re lucky enough—or if you pay attention to my story here—you might come to realize that death can sanctify life.

I didn’t grasp this even by a thin hair, however, when it came to my own mom. It took me years to assimilate the fact that she would die one day. It just seemed . . . impossible. But my mom was human, and she died from Alzheimer’s.

I was rising up the corporate ladder in my thirties in California while my mom was spinning down a dark rabbit hole with this unrelenting affliction. I’d started to notice during visits that little things were “off” with Margaret. She was becoming forgetful and easily aggravated, which was unusual for an unfussy person. Still, I had no idea that I was actually witnessing the beginning of her end.

As her short-term memory continued to fail, my mom announced that she was coming down with CRS (Can’t Remember Shit). If I could rename Alzheimer’s, that’s what I’d call it. Having a funny acronym for the disease that would eventually kill her was my mom’s way of denying its existence. So it was no surprise that when the doctor first suggested that she might have Alzheimer’s, she took one look at him and said: “Fuck you.” Then she stomped out of his office. Still, there was no denying the slow ravage of this abysmal disease.

There are seven stages of Alzheimer’s, in case you’re wondering. The first stage is called “normal outward behavior.” In short, there are no changes in behavior. Whoever identified these stages should have said that there are six stages of Alzheimer’s, because what the hell is the point of the first stage being “normal”?

The second stage is called “very mild changes.” That’s self-explanatory: We’re talking stuff like misplacing keys or forgetting a word. I think I’ve been in this stage since menopause. The third stage is called “mild decline”: Good-bye, short-term memory. The fourth through seventh stages are a series of increasingly shitty degenerations, from “moderate,” to “moderately severe,” to “severe,” to “very severe.” Those last three stages might as well be called the Black Ice Period. Slippery slope doesn’t even come close to describing that southerly descent.

My mom kept up the denial for years. Suzanne and I had to constantly manipulate her to get basic things done, like steal bills out of her office to make sure they got paid. When I told her that it was probably time to stop driving, she looked at me incredulously. “Why?” she asked.

“Well, you know, you’ve had some memory issues.”

“No I haven’t.”

“Yes you have.”

The next day, she drove her car to a dealership and bought herself a new one. That was my mother. “Bullheaded” is one word that comes to mind.

In A Prayer for Owen Meany, John Irving writes:

When someone you love dies, you don’t lose her all at once; you lose her in pieces over a long time—the way the mail stops coming, and her scent fades from the pillows and even from the clothes in her closet and drawers. Gradually, you accumulate the parts of her that are gone. Just when the day comes—when there’s a particular missing part that overwhelms you with the feeling that she’s gone, forever—there comes another day, and another specifically missing part.

Irving wasn’t describing Alzheimer’s, but he might as well have been.

You could fill a library with books written about how to find the right job or fix your marriage, or what to expect when you’re expecting a baby (never mind the massive pile of books about how to raise that baby once it starts growing up). But back then there weren’t many books about how to deal with a dying parent. There was no How the Fuck to Stay Sane and Not Collapse with Grief When Your Parent Has Alzheimer’s. I was completely unprepared for this. All I retained from my reading at that time was this line that I’d read in a medical journal: “100 percent mortality rate.”

For ten years I witnessed my mother die a slow death. By the time 2010 rolled along, I was emotionally vacant. I remember driving on the freeway with Suzanne one day when I turned to her and said: “The joke’s on me.” The joke was simple: I’d broken up not just with the church and organized religion, but with God. I had turned my back on God, so God had done the same to me.

Now, let’s take a quick station break while I possibly piss some of you off. (Yes, I’m talking to some of you Christians.) We all have our interpretations of what “God” is—or isn’t—based on our faith, religion, and upbringing. It’s a loaded word, that’s for sure. In her book Help, Thanks, Wow, writer Anne Lamott took a shot at defining what it means for those who find the word too “triggering or ludicrous a concept.” How about we consider God, she helpfully suggested: “The Good, the force that is beyond our comprehension but that in our pain or supplication or relief we don’t need to define or have proof of or any established contact with. Let’s say it is what the Greeks called the ‘Really Real,’ what lies within us, beyond the scrim of our values, positions, convictions, and wounds. Or let’s say it is a cry from deep within to Life or Love, with capital L’s.”

Lamott concludes that it doesn’t really matter what we call this force. “I know some ironic believers who call God Howard, as in ‘Our Father, who art in Heaven, Howard be thy name.’ ” She adds that a friend of hers refers to God as “Hairy thunderer or cosmic muffin.”

I was most definitely crying “from deep within to Life or Love, with capital L’s” as my mom was dying. I’d ignored the cosmic muffin for years, then realized that, shit, maybe I could use

a little help. Inside I was asking, or maybe I was imploring: “Are you there, God? It’s me, asking about Margaret.” (Yeah, I loved Judy Blume, too.)

By 2011, I was back in Oklahoma and seriously grappling with these existential issues because my mom was in hospice. I would have rather eaten crushed glass than associate my mom with that word, but there was no denying it: She was heading through that thin veil between life and death.

I flew from California to Oklahoma one very shitty winter day to be by her bedside with her caretaker and my best friend, Cubby, whom I met when I was nine years old. Our mothers were the first to notice our connection when the two of us were practicing our short game on the putting green of our “country club” in Oklahoma. (Imagine a 1970s-style Sizzler steak house in the middle of a clean-cut field and you get the picture.)

“You know, I think those girls are going to be best friends their whole lives,” Cubby’s mom said. To which my mom replied: “I couldn’t agree with you more.”

We’ve since gone through every phase of life together, from getting high the first time on Mexican dirt weed and RV camping in the Ozarks, to protecting each other against mean girls and having kick fights behind the backstop of baseball fields. (Cubby always won because she’s all legs.) Many boyfriends later, we both came out to each other at more or less the same time. (I had an inkling about Cubby and her “girl pal” all along), then tormented our mothers by suggesting that we’d been lovers since elementary school. There were no secrets that we didn’t share (that’s still the case) and no limits to what we’d do to help each other (ditto). We’ve cried on each other’s shoulders in love and pain and have cracked up so hard we’ve peed in our pants. (Come on, I know you’ve done it, too.)

So of course Cubby was with me that day when my mom was at home in hospice. Oklahoma was experiencing the worst snowstorm in a century at the time: A state of emergency was declared as roads were shut down and snow piled up to the rafters. We lived on powdered doughnuts, Mountain Dew, and spray cheese. That’s what pain tastes like, in case you were wondering.

One sleepless night during that period I was lying next to my mom in her bed playing her favorite Anne Murray song from my childhood. She was also a big fan of Barry Manilow and Neil Diamond. To this day I love them all. At around 2:00 a.m., unable to come to grips with the idea that the so-called Grim Reaper was zeroing in on my mom, I got a call from my dear friend Mona.

I’m going to make a wild assumption that you’ve probably had a Mona in your life at some point. Mona is that person who bursts into your life unexpectedly and changes it almost by accident (and sometimes precisely because of an accident, as you’ll understand shortly).

Mona was blond, bubbly, and loved baubles. She had a red convertible that looked like something a high-priced hooker would drive. She wore Jane Fondaish workout gear and ripped clothes way before ripped clothes became a fashion statement, and she was very 1980s in her clothes and color palate: electric blue and radiant orchid. Pantone calls the colors of that decade “vibrant and saturated, reflecting prosperous times and an upbeat mood.” That was Mona to a T.

An accomplished singer, pianist, life coach, and psychic, Mona was always the life of the party. Imagine an entertainer with a huge heart and a dash of schmaltz and that’s Mona. Oh, and an added bonus: Mona was also a lesbian, which she embraced later in life.

When Suzanne and I moved to LA, we ended up living twelve houses down from her and her girlfriend.We met her haphazardly through her girlfriend, who saw Suzanne and me kissing each other good-bye in our driveway. Mona’s girlfriend was jogging up the hill and stopped to gawk at us. You could almost hear her thinking out loud: Oh goody! Two girls! She told us that she and her girlfriend, Mona, lived up the street; how about we come over and hang out?

Suzanne and I didn’t have any lesbian friends back then, which I guess made us bad lesbians. But once we met Mona we became fast friends.

So here’s the deal with Mona: When she was twenty-five, she was almost killed by a serious magnesium deficiency. Lying in the hospital on the brink of death, she experienced an NDE. Before meeting Mona I thought that NDE stood for network data element. When I found out that it actually stands for “near-death experience,” I figured it had something to do with choking on a ham sandwich and having to undergo the Heimlich maneuver.

In the 1960s and ’70s, Swiss American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was among the first to study near-death experiences—or what was then referred to as “out-of-body experiences.” She wrote the hugely influential book On Death and Dying, and was the first to articulate what’s now commonly referred to as “the five stages of grief.” Raymond Moody, who wrote the bestseller Life After Life, was later credited with having popularized the term “near-death experience.” His book documented one hundred people who experienced “clinical death,” were revived, and went on to recount what happened in that zone between life and death. Tons of books have since been written and research studies conducted, including clinical studies in hospitals that tested the consciousness, memories, and awareness of people who were clinically dead in a state of cardiac arrest.

When Mona told Suzanne and me about her NDE, I was what we Oklahoma peeps like to call “shit-shocked.” She described how, lying on the hospital bed, she rose out of her body. Looking down on it as she hovered above, she saw ribbons of liquid gold emanating into her head, which was hinged open like an oven door. Then she had a series of experiences whose characteristics have been recorded by nearly every culture all over the world and share the same traits. Here’s what they are:

The distinct awareness of leaving one’s physical body (in the case of clinical trials, lots of patients described exactly what was said and done by medical professionals during resuscitation efforts).

Feelings of intense peace and unconditional love.

A rapid movement toward a powerful light, often through a passageway or a tunnel.

Encountering spirits, mystical beings, “ghostly orbs,” or deceased loved ones.

Receiving knowledge about one’s life and the nature of the universe.

Approaching a border or a decision by oneself or spirits to return to one’s body, often accompanied by a reluctance to return.

People on both sides of the scientific divide consider NDEs both a confirmation that human consciousness continues after death and a glimpse into the spirit realm where souls travel after death. Mona was unequivocally convinced of this. Like others, she was reluctant to return to her body during that experience, but was “told” by an energetic force that she had to go back. And when she finally did return to her body, she came back with uncanny “knowledge about life and the nature of the universe.” She had intuitive psychic abilities that gave her insights into people’s lives and their psychological makeup, without knowing those people. She was keyed into the wisdom of various world religions without having read about them; she could “see” and feel things before they happened.

Anita Moorjani is another woman who had a remarkable NDE, which she chronicled in her book Dying to Be Me. After she waged a four-year fight, her body was riddled with cancer when she finally “succumbed”: Moorjani was clinically dead when she had her NDE. Miraculously, within weeks of regaining consciousness, she was released from the hospital with no trace of cancer. She went on to write her book about the experience and her incredible insights about our physical and metaphysical world (including the actual cause of her cancer) that she garnered during her NDE.

Moorjani also went on to frame the immensity of the unseen world in which we all live during a TED talk. “Just imagine that right now you’re in a warehouse that’s completely pitch-black,” she said. “In your hand you hold a little flashlight . . . and with that flashlight, you navigate your way through the dark.” All that we could see, Moorjani points out, would be whatever is illuminated by the flashlight beam; everything else would be in total darkness. “But imagine that one day a big floodlight goes on,” Moorjani continues, “and

the whole warehouse is illuminated, and you realize that this warehouse is huge. It’s bigger than you ever imagined it to be . . .” The warehouse is filled with countless completely amazing and stupefying things—some things we’ve never seen or imagined before; other things that we recognize, for better or for worse. “Then imagine if the light goes back off again, and you’re back to one flashlight,” Moorjani says. You’re again seeing the narrow view of whatever is illuminated by that beam of light, but “at least you now know that there is so much more that exists simultaneously and alongside the things that you can’t see.”

Those words would later turn out to be almost prophetic in my case, though I’ve never had an NDE. However, when I first heard about the phenomenon from Mona, I wondered if NDEs were an LA thing, like kale colonics and juice cleanses. I mean, honestly: Is there something about LA that makes people get in touch with their inner Shirley MacLaine (whom I love, by the way)? If you told someone in Oklahoma that you’d had a near-death experience, they’d probably tie you in a straitjacket and send you out of state.

Mona notwithstanding, my association with psychics then was still essentially zero. I’d drive right by those psychic shops that are all over LA without a glance on my way to the supermarket, usually for black licorice and tequila. I’d balance those out with Atkins bars and throw in Nicorette gum once in a while—cherry flavored, because it goes better with Diet Coke—and an orange Hostess cupcake if I was having a hard day. That’s when I’d eat my feelings. (It’s also why I’m not skinny. I have a lot of feelings to eat. By the way, an orange Hostess cupcake is a fruit. In fact, it’s a citrus.)

I now have far more perspective and think LA is the perfect place to learn about mind-blowing experiences, because it’s filled with more creative, psychic, intuitive, talented (and yeah, flaky, freaky, and flamboyant) people per capita than any other place on earth. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright once said: “Tip the world over on its side and everything loose will land in Los Angeles.”

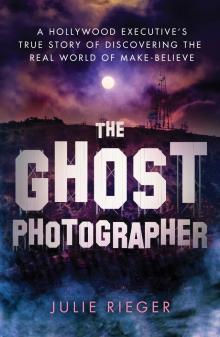

The Ghost Photographer

The Ghost Photographer